Michael Fumento

Factual · Powerful · Original · Iconoclastic

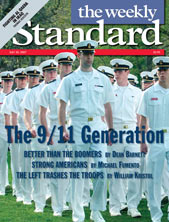

Issues confronting the U.S. military.

October 27, 2006 · Michael Fumento · Military  In the film “Home of the Brave,” a soldier who lost her hand in Iraq is asked if she underwent physical rehabilitation at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. “Yeah, Walter Reed,” she says. “Talk about tough Americans.” Tough Americans, indeed.

In the film “Home of the Brave,” a soldier who lost her hand in Iraq is asked if she underwent physical rehabilitation at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. “Yeah, Walter Reed,” she says. “Talk about tough Americans.” Tough Americans, indeed.

When I visited that same ward the first soldier I met was Sgt. Luke Shirley, who had stepped on an improvised explosive device (IED) blowing off his right side appendages and spraying him with shrapnel. “It kinda sucks not having an arm or leg,” he told me, “but it hasn’t bothered me like you’d think it would.” Just offhand, I would think it would have devastated him. I was dumbstruck. What kind of person is this?

That’s why I visited Walter Reed’s Orthopedic Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Ward in Washington, D.C, along with the surgical inpatient ward at the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. (At Bethesda the men and women aren’t yet ready to be sent on to Walter Reed or elsewhere for rehabilitation.) I wanted to meet these tough Americans and tell some of their stories.

It was something I had long put off, because I go to war zones as an embedded reporter.

A soldier (middle) a Marine (far right) and Iraqi Army soldiers in the dirty and dangerous city of Karma in 2006. Photo by Michael Fumento. Click for larger image.

A soldier (middle) a Marine (far right) and Iraqi Army soldiers in the dirty and dangerous city of Karma in 2006. Photo by Michael Fumento. Click for larger image.

I have no problem facing my own mortality for, as Ebenezer Scrooge’s nephew Fred observed, we are all “fellow-travelers to the grave.” But losing an arm or leg or eyeball, ah, that’s another thing entirely. I believed I would come away from the wards feeling sick and more hesitant about upcoming embeds. Instead, each time I walked out it was with a feeling of elation at the attitudes I saw in Americans who not only refused to see themselves as victims but rather embraced their injuries as challenges.

Please note that at neither hospital was I allowed to pick interview subjects. For instance, while I asked for a female interview subject and there were female patients, I couldn’t talk to any. Further, there was an administrator with me at all times. Surely there were disgruntled patients in both wards at that or some other time. But the Walter Reed ward I visted was in no way implicated in the recent scandal, which concerned a completely different building, and I don’t doubt the sincerity or veracity of those whom I did interview.

Sgt. Luke Shirley, U.S. Army

I only got a few minutes with Shirley before he had to leave. A member of the 10th Mountain Division (Light Infantry) from LaBelle, Florida, he was at 28 the oldest person I interviewed. He joined the Army in 1998 because “I got tired of having a normal job.” A few days before Christmas last year he was on a foot patrol south of Baghdad. “We were looking for people who attacked our unit. I was lead and couldn’t see much,” he said. “Suddenly an IED threw me about 25 feet. I didn’t know the extent of the damage until I got to the hospital. All I asked was ‘Is my “stuff” still there?’”